IN PRAISE OF THE DIAGONAL

22.09.2022 POSITANO

It’s the diagonal lines.

If that sounds like a controversial statement, try to think of a truly iconic view that has none. Even deserts have dunes, while the monotonous march of the Salar de Uyuni salt flats in Bolivia are lent depth, and texture, and interest, by the irregular honeycombed cracks in the surface that snake in uneven diagonals across their surface.

The J. Paul Getty Museum’s online ‘Elements of Art’ course teaches us that “diagonal lines convey a feeling of movement. Objects in a diagonal position are unstable. Because they are neither vertical nor horizontal, they are either about to fall or are already in motion”. NYU professor Alexander Galloway writes that “The diagonal is a dynamic force that grants access to several important domains, namely relation, contradiction, and the irrational. Perhaps this is why the diagonal has long figured prominently in esoteric and mystical practices. Triangles, pyramids, and pentagons… seem to awaken forces of spiritual insight if not the occult”. Aspiring photographers are taught about the dynamic power of diagonals within the perpendicular box of the image frame. The upward bottom left to top right sweep is widely considered to be the strongest axis.

View

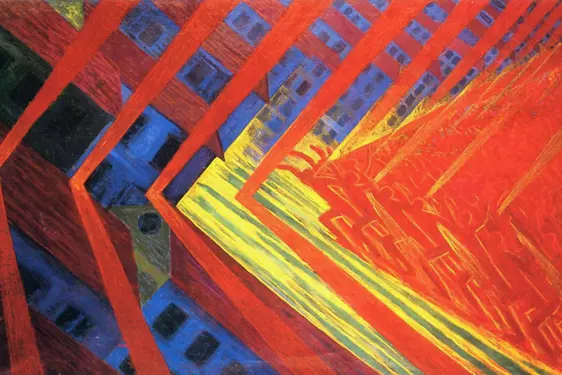

Arguably, it was the diagonal that underpinned two revolutions in art: the discovery of the correct laws of perspective in the early Renaissance, and the early 20th-century avant-garde. Italian Futurism and Russian Constructivism both exploited diagonal forces in painting and sculpture as vectors of the new machine-age cult of speed, and metaphors for social change. In Luigi Russolo’s 1911 canvas La Rivolta (above), whole buildings have their axes tilted as they are caught up in the revolutionary thrust of the arrows that reverberate like sound waves across the surface of the painting.

Even Cézanne, painting decades earlier, sensed the power of the diagonal. Not only was it a defining character of one of his recurrent subjects – the peak of Mont Sainte-Victoire near Aix-en-Provence – but it was embedded in his very technique. Analysing a series of the French artist’s paintings held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, conservationist Marigene H. Butler noted in 1984 that by relatively early in his career, Cézanne had evolved a style that involved “patches of parallel strokes, often applied on the diagonal, which laid down each color in turn, brushing the edges of adjacent color patches into one another, wet into wet, thoroughly covering the canvas with paint”.

View

Oftentimes, in a great view, it’s the receding diagonal lines (as in all those Italian Renaissance Annunications) that give the scene interest and lend it a sense of movement. Think of the Taj Mahal: it’s an incredible building, but what elevates it to world ‘iconic view’ status is the image that springs to mind the moment you name it: that frontal view from the far end of the Hawd al-Kawthar water tank. The mirrored surface of the water, the trees, lawns and paths of the formal gardens that surround it: all converge on the pure white mausoleum in the distance. The latter’s dome, spires and minarets continue the dynamic thrust. Everything pulls skywards. The same goes for the Eiffel Tower: the variant here being that the famous building itself is a play of diagonals. And although it’s a marvel of medieval Romanesque architecture, would the Leaning Tower of Pisa be as celebrated as it is if it didn’t… well, lean?

View

What happens when you remove the diagonals from the landscape? In around 1980, Japanese artist Hiroshi Sugimoto launched an ongoing project called Seascapes. For forty years now, he has been setting up his box camera on beaches and cliffs around the world and taking black and white photographs of the sea and sky, always in the same horizontal format, always with the frame divided into two equal halves. The project became a news item in 2009 when rock group U2 used one of the works, Boden See, Utwill, as the cover of their album No Line on the Horizon.

Sugimoto’s Seascapes are landscapes as abstract art – beautiful, haunting, tranquil, like a painting by Rothko. They are minimalist views, shorn of movement, action, dynamism. And yet even they can’t suppress the diagonal entirely: in some of the works in the series, contrary wavelets striate the seas, challenging the geometric cage they are boxed into.

What makes the view from Le Sirenuse so fascinating is the way it combines the peaceful abstract minimalism of Sugimoto’s seascapes with the exhilarating dynamism of a Futurist arrow. To the left is the line of the sea and sky, varied on the horizon by the undulating silhouette of the Li Galli islands. To the right is a sudden diagonal thrust, a one-sided pyramid of brightly coloured houses. On mornings when the rising sun peeps out from under the blanket of a stormy sky, as in our header image, the contrast between the illuminated houses and the dark sea and sky appears so great that it’s difficult not to see it as a montage, two separate photos artfully stitched together.

It’s a view we simply cannot get enough of, because it is constantly changing: through the seasons, over the hours of the day, sometimes in a handful of seconds as the sun peeps through clouds and light dapples the sea, the maiolica church dome, the jaunty stack of houses, in a series of endless variations that are never repeated. Long live the diagonal!

Positano view © Roberto Salomone

Le Sirenuse Newsletter

Stay up to date

Sign up to our newsletter for regular updates on Amalfi Coast stories, events, recipes and glorious sunsets